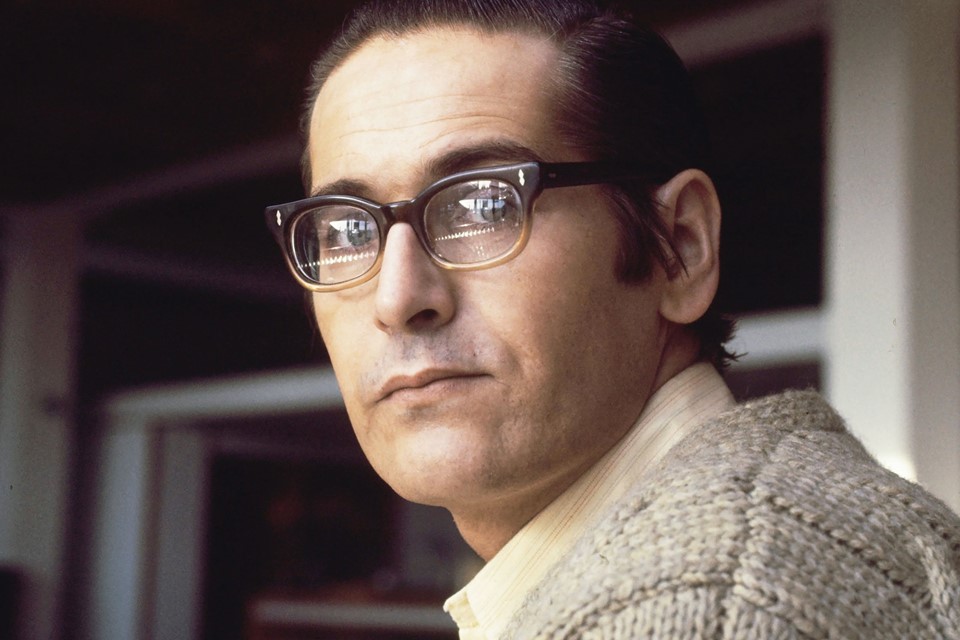

Bill Evans (1929-1980) was an American jazz pianist and composer, widely regarded as one of the most influential jazz musicians of the 20th century. Known for his lyrical playing, harmonic sophistication, and innovative approach to the piano trio format, Evans played a crucial role in the development of modern jazz. His work, particularly during the late 1950s and 1960s, has had a profound and lasting impact on jazz pianists and musicians across genres.

Overview of Bill Evans

- Early Life and Career Beginnings: Born William John Evans on August 16, 1929, in Plainfield, New Jersey, Bill Evans began studying piano at a young age, demonstrating exceptional talent early on. He studied classical piano and graduated with a degree in music from Southeastern Louisiana University in 1950. After a stint in the U.S. Army, Evans moved to New York City in the mid-1950s, where he became involved in the jazz scene. He initially worked as a sideman with musicians like Tony Scott and George Russell, gaining recognition for his introspective and harmonically advanced style.

- Breakthrough with Miles Davis and Kind of Blue: Evans’ big break came in 1958 when he joined Miles Davis’s sextet, contributing significantly to the landmark album Kind of Blue (1959). The album, widely regarded as one of the greatest jazz recordings of all time, featured Evans’ modal approach and delicate, impressionistic touch, particularly on tracks like “So What” and “Blue in Green.” Evans’ influence on the album’s sound and his collaboration with Davis helped to shape the direction of modern jazz, particularly in the use of modal harmony and space in music.

- Formation of the Bill Evans Trio: In 1959, Evans formed his first piano trio with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, a group that would revolutionize the jazz trio format. Their recordings, particularly the albums Portrait in Jazz (1960) and Sunday at the Village Vanguard (1961), showcased a new level of interplay and communication between the musicians, with each member contributing equally to the group’s dynamic sound. The trio’s approach emphasized a conversational style of playing, where the bass and drums were given greater independence and improvisational freedom, laying the groundwork for the modern jazz trio.

- Tragic Loss and Continued Innovation: The death of Scott LaFaro in a car accident in 1961 deeply affected Evans, leading to a brief hiatus from performing. However, he soon returned to music with a renewed focus, forming new trios with notable bassists such as Chuck Israels, Eddie Gómez, and later Marc Johnson. Evans continued to explore and refine his harmonic language, incorporating influences from classical music, particularly the works of Debussy and Ravel. His later albums, such as Waltz for Debby (1961), Conversations with Myself (1963), and You Must Believe in Spring (1977), are celebrated for their emotional depth and technical brilliance.

- Later Years and Legacy: Throughout the 1970s, Evans remained a prolific performer and recording artist, despite ongoing struggles with addiction. His music during this period continued to evolve, displaying a profound sense of lyricism, introspection, and a deep connection to melody and harmony. Evans’ contributions to jazz were recognized with multiple Grammy Awards, and his influence extended to generations of jazz pianists, including Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea. Bill Evans passed away on September 15, 1980, from complications related to his addiction, leaving behind a rich legacy that continues to inspire musicians worldwide.

Impact on Music and Culture

- Redefining the Jazz Piano Trio: Bill Evans’ work with his trios, particularly the groundbreaking group with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian, redefined the jazz piano trio. Their collaborative approach, where each instrument played an integral role in the conversation, set a new standard for interaction and creativity in small group jazz. This approach influenced countless jazz trios that followed, making Evans a pivotal figure in the evolution of jazz.

- Harmonic Innovation and Influence: Evans was a master of harmony, often drawing on his classical training to create complex, yet accessible, harmonic structures. His use of modal harmony, voicings, and chord extensions expanded the harmonic vocabulary of jazz, influencing not only pianists but also composers and arrangers. His work is often studied for its harmonic richness and subtlety, and his approach has had a lasting impact on jazz education.

- Emotional Depth and Lyricism: One of Evans’ most significant contributions to jazz was his ability to convey deep emotion and lyricism through his playing. His touch, phrasing, and use of space in music created a unique voice that resonated with listeners on a profound level. Evans’ ability to blend technical mastery with emotional expression made his music timeless, and his recordings continue to be revered for their beauty and emotional impact.

- Influence on Modern Jazz and Beyond: Bill Evans’ influence extends far beyond the jazz world. His approach to harmony, melody, and form has impacted musicians across genres, including classical, pop, and rock. His compositions, such as “Waltz for Debby” and “Peace Piece,” have become jazz standards, and his interpretations of popular songs have redefined how jazz musicians approach the Great American Songbook.

- Cultural Legacy and Recognition: Evans’ contributions to jazz have been widely recognized, and his music continues to be celebrated through reissues, tributes, and academic studies. He was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994, and his recordings are considered essential listening for anyone interested in jazz. Bill Evans’ legacy as a musician who blended technical innovation with emotional depth remains influential to this day.

References

- Pettinger, Peter. Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. Yale University Press, 1998.

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett: The Man and His Music. Da Capo Press, 1992. (Includes context about Evans’ influence on Jarrett)

- Giddins, Gary. Visions of Jazz: The First Century. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Watson, Ben. Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. Verso, 2004. (Discusses Evans’ impact on improvisation)

- Lees, Gene. Meet Me at Jim & Andy’s: Jazz Musicians and Their World. Oxford University Press, 1988.

Leave a Reply